Somalia stands at a crossroads. For the first time in 56 years, the government is attempting to transition to direct elections, a one-person, one-vote system that would fundamentally reshape how ordinary citizens engage with democracy. President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has championed this reform as central to national reconstruction, with local council elections already underway and voter registration cards being distributed across Mogadishu. Yet this noble ambition has fractured the nation’s political leadership, alienated key regional actors, and raised legitimate security concerns that cannot be ignored.

Rather than pursue an all-or-nothing approach to direct elections, Somalia should adopt a pragmatic hybrid model: implement one-person, one-vote elections at the local and municipal levels while maintaining traditional indirect voting for presidential and federal state leadership. This measured path offers the best chance of achieving democratic progress while preserving national unity at a critical moment.

The Case for Caution

The opposition to direct elections is not monolithic or merely obstructionist. Former President Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, who leads the opposition coalition, has articulated concerns that deserve serious consideration. In recent statements, he warned that Somalia is “at a dangerous point,” citing ongoing insecurity and political fragmentation as obstacles to credible elections. His Council of National Salvation has rejected the current electoral framework, arguing that the country lacks adequate consensus on both electoral and constitutional reforms.

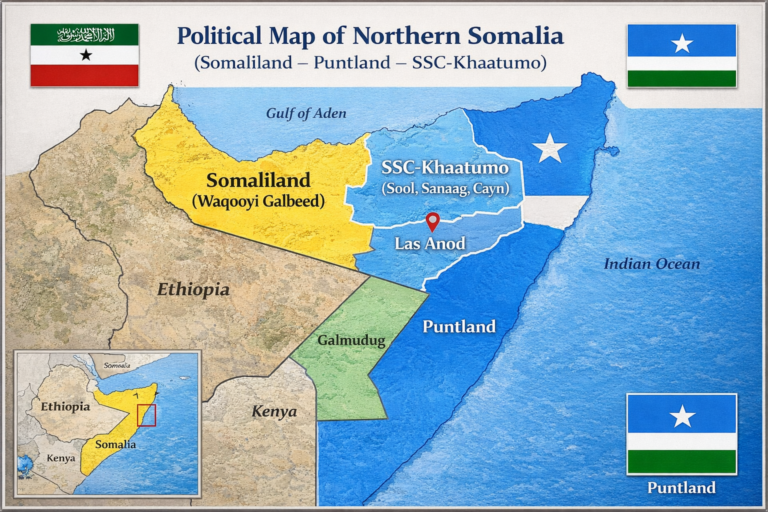

Moreover, two critical regional powers have effectively boycotted the process. The presidents of Puntland and Jubaland, semi-autonomous federal member states, have rejected the electoral framework and refused to participate in discussions. This is not a minor inconvenience. These states control vast territories and significant populations. Proceeding without their buy-in risks deepening the very fragmentation that threatens Somalia’s stability.

The security situation remains precarious. While the government reports progress against Al-Shabaab in certain areas, the jihadist group continues to mount attacks. The African Union’s stabilization mission is in transition, creating uncertainty about sustained counterterrorism efforts. Holding nationwide direct elections in this environment demands exceptional security architecture and public confidence, both of which remain lacking.

The Strength of the Hybrid Approach

A hybrid model acknowledges these realities without abandoning democratic reform. The government could immediately move forward with one-person, one-vote elections at local and municipal levels, beginning with the Banaadir region’s ongoing efforts. This delivers meaningful democratic participation to ordinary citizens where security can be more effectively managed and local issues resonate most with voters. Local elections serve as a testing ground for new voter card systems and electoral procedures, reducing the risk of nationwide complications.

Presidential and federal state elections could remain under the existing indirect system, at least temporarily. This preserves consensus-building among political elites, a mechanism that has proven valuable in Somalia’s fragile context. Rather than viewing this as a retreat, it should be framed as a sequenced transition: prove that direct voting works locally, build confidence in the system, negotiate consensus on national elections, then expand the model upward.

This approach offers several practical advantages. First, it gives the government time to address opposition concerns through dialogue rather than confrontation. Second, it allows Puntland and Jubaland room to participate without abandoning their positions, as they could accept local direct elections while maintaining their reservations about presidential elections. Third, it reduces the security footprint required, concentrating resources on protecting more limited voting processes. Fourth, it demonstrates democratic commitment without gambling the nation’s fragile unity on an untested nationwide system.

Managing the Political Landscape

President Mohamud’s commitment to democratic reform is admirable, but political leaders sometimes must choose between moving fast and moving wisely. The opposition’s Kismayo conference scheduled for December 17 signals that stakeholders remain engaged, a sign that negotiation is possible if the government shows flexibility. Rigid insistence on immediate nationwide direct elections risks pushing these actors further into opposition and could destabilize the very regions where elections are planned.

The government’s argument that electoral reform strengthens state institutions is valid. But institutions are also built through consensus and inclusion. A hybrid approach that brings regional leaders and opposition figures into the electoral process, rather than excluding them, ultimately creates stronger institutions than a system imposed against significant resistance.

A Measured Vision for Democracy

Somalia deserves democracy. Its citizens deserve the right to choose their leaders directly. But post-conflict transitions require sequencing, patience, and pragmatism. Venezuela does not become Denmark overnight. The hybrid approach recognizes that Somalia can honor its democratic aspirations while respecting current realities: limited security, competing power centers, and the need for broad political consensus.

Local direct elections offer real democratic progress. Citizens in Mogadishu, Kismayo, and other municipalities would genuinely exercise political power over local affairs. This foundation can support expansion to national elections once political consensus solidifies and security improves. Meanwhile, maintaining indirect presidential elections preserves a mechanism that has allowed Somalia to navigate leadership transitions without collapse.

The measure of democratic success is not the speed of reform, but its durability. A staged transition that brings all major political actors into the process will ultimately produce more legitimate, stable democratic institutions than a contested nationwide system that fractures the political consensus Somalia has painstakingly rebuilt.

The path forward requires wisdom: embrace direct elections where they can succeed, preserve indirect mechanisms where consensus remains essential, and negotiate a timeline that all major stakeholders can accept. This is not timidity. It is the pragmatism that has allowed Somalia to survive and begin to thrive.