The death penalty in Somalia has become a glaring symbol of a justice system in crisis. Recent cases have exposed fundamental flaws that demand urgent attention: individuals with untreated mental illness are being sentenced to death, investigations are inadequate, and the irreversible nature of execution leaves no room for the correction of mistakes. As the international community moves steadily toward abolition, Somalia must confront a difficult question: can we continue to justify capital punishment when our system fails to protect the most vulnerable?

The Global Tide Turning Against Execution

The momentum against the death penalty is undeniable. According to Amnesty International, 113 countries had abolished capital punishment in law by the end of 2024, representing more than half the world’s nations. When Amnesty began its work in 1977, only 16 countries had taken this step. The organization’s position is unequivocal: the death penalty represents the ultimate cruel, inhuman, and degrading punishment that breaches fundamental human rights, particularly the right to life and freedom from torture.

International law recognizes that execution is irreversible, and mistakes happen. Since 1973, more than 200 people sent to death row in the United States have later been exonerated or released on grounds of innocence. If this occurs in a country with extensive legal resources and appeal processes, what does it mean for Somalia, where investigations are often rushed and proper legal representation is scarce?

The death penalty also fails as a deterrent. Countries that execute routinely cite deterrence as justification, yet this claim has been repeatedly discredited. There is no evidence that capital punishment is any more effective in reducing crime than life imprisonment. What it does accomplish, however, is finality without the possibility of redemption or correction.

Mental Illness and the Death Chamber: Somalia’s Invisible Crisis

Perhaps no issue exposes the cruelty of Somalia’s death penalty more starkly than the sentencing of individuals with mental illness. As Geeddi SPN noted on social media, many people with mental illnesses are sentenced to death in Somalia without basic psychological evaluations. This represents a profound failure of justice.

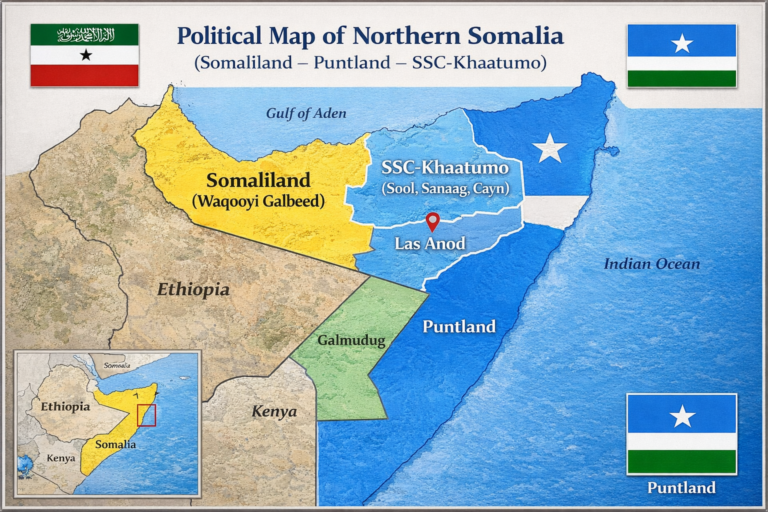

The case of Hassan Abdullahi Abdi Shire illustrates this crisis with devastating clarity. The 37-year-old Danish-Somali citizen was arrested in Kismayo in June 2023 for the killing of his mother, Halimo Mohamed Omar. The circumstances surrounding this tragedy reveal a system that failed at every turn.

Shire had been brought to Somalia from Denmark a year earlier and placed in a rehabilitation center, where he allegedly endured confinement and continuous physical abuse. Authorities suspect he suffers from mental illness, yet there is no indication that he received proper psychiatric care or evaluation. Instead, he was kept in conditions that may have exacerbated his condition. When his mother returned from Denmark, the tragic outcome seemed almost inevitable.

Following his arrest, a police officer declared that Shire “must face the harshest sentence,” potentially including the death penalty. But executing someone with untreated mental illness is not justice. It is the elimination of a person who needed medical intervention, not a death sentence. International human rights law prohibits the use of capital punishment against people with mental and intellectual disabilities, yet Somalia continues this practice.

The so-called “Dhaqan celis” rehabilitation centers, where Shire was held, have become sites of documented abuse. In January 2020, nine Somali girls from the UK, Denmark, Sweden, and Canada escaped from one such center in Mogadishu after overpowering a guard. These facilities, estimated to number in the hundreds across Somali cities, operate with minimal oversight and have been associated with reports of violence, abuse, and even rape.

When mentally ill individuals are funneled through this system and then into a criminal justice process that lacks proper psychiatric evaluation, the death penalty becomes not a tool of justice but an instrument of systemic failure.

Flawed Investigations, Irreversible Consequences

The recent case of Hodan Mohamud Diriye in Galkayo further demonstrates how Somalia’s rush to execution can override proper investigation and consideration of circumstances. The First Instance Court of Galkayo sentenced the 34-year-old mother of twelve children to death in November 2024 for the killing of 14-year-old Sabirin Saylan Abdulle.

While the crime itself was undeniably serious and the evidence included video footage and the defendant’s confession, the speed of the process raises concerns. The case appeared before the court on November 20, just days after public protests demanded justice, and a death sentence was handed down by November 24. This timeline suggests a system responding to public pressure rather than conducting the thorough investigation such an irreversible sentence demands.

What mental health evaluation did Hodan receive? What circumstances in her life as a mother of twelve children might have contributed to this tragedy? Was she provided with adequate legal representation to explore all aspects of her case? These questions appear to have been secondary to the demand for swift punishment.

The international standards are clear. Amnesty International emphasizes that in many cases worldwide, people are executed after being convicted in grossly unfair trials, on the basis of torture-tainted evidence, and with inadequate legal representation. In some countries, death sentences are imposed as mandatory punishment for certain offenses, preventing judges from considering the circumstances of the crime or the defendant.

Somalia’s justice system, operating under immense pressure and limited resources, is particularly vulnerable to these failures. When investigations are inadequate, when mental health is ignored, and when the accused lack proper legal defense, the risk of executing someone who should not die becomes unacceptably high.

The Discriminatory Weight of Capital Punishment

The death penalty does not fall equally on all members of society. As Amnesty International documents, the weight of capital punishment is disproportionately carried by those with less advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds or belonging to marginalized groups. This includes having limited access to legal representation and being at greater disadvantage in their experience of the criminal justice system.

In Somalia, where poverty is widespread and legal resources are scarce, this disparity is magnified. Those who can afford quality legal representation have a fundamentally different experience of the justice system than those who cannot. When the punishment is death, this inequality becomes a matter of life and death determined by circumstance rather than justice.

A Better Alternative: Life Imprisonment

Life imprisonment offers everything the death penalty claims to provide, without its irreversibility and cruelty. It protects society from dangerous individuals. It allows for punishment proportionate to serious crimes. Most importantly, it preserves the possibility of correcting mistakes.

When new evidence emerges, when mental illness is properly diagnosed, when investigative failures come to light, life imprisonment allows for justice to be served through release or sentence modification. The death penalty allows only for posthumous apologies, a cold comfort to families and an admission of a failure that can never be remedied.

For individuals with mental illness, life imprisonment creates the opportunity for treatment, evaluation, and potentially rehabilitation. Execution forecloses all these possibilities, turning a medical and social failure into a permanent injustice.

The Call to Action

Somalia stands at a crossroads. The country can continue down a path that 113 nations have already abandoned, or it can join the global majority in recognizing that the death penalty has no place in a just society.

The first step is immediate: mandatory psychological evaluations for all defendants in capital cases. No person with untreated or undiagnosed mental illness should face execution. This is not merely a matter of international law; it is basic human decency.

Second, Somalia must strengthen its investigative processes and ensure adequate legal representation for all defendants in capital cases. The irreversibility of execution demands nothing less than the most thorough and fair proceedings possible.

Third, Somalia should impose a moratorium on all executions while conducting a comprehensive review of cases involving mental illness, inadequate investigation, or procedural failures. History has shown that such reviews inevitably uncover cases that should never have resulted in death sentences.

Finally, Somalia should begin the process of full abolition. The death penalty does not make Somalia safer. It does not deter crime more effectively than life imprisonment. What it does accomplish is the elimination of human beings in a system that has repeatedly demonstrated its inability to guarantee fairness, thoroughness, or justice.

Conclusion: Choosing Justice Over Vengeance

The recent cases in Galkayo and Kismayo are not arguments for the death penalty. They are arguments against it. They reveal a system that sentences the mentally ill, rushes to judgment under public pressure, and implements an irreversible punishment despite glaring inadequacies in process and protection.

As Geeddi SPN wrote, “The death penalty is not the solution.” This statement reflects a growing understanding within Somalia that capital punishment represents not strength but failure: failure to provide mental health care, failure to conduct proper investigations, failure to ensure fair trials, and failure to recognize the irreversible nature of the punishment we impose.

The path forward is clear. Somalia must abolish the death penalty and replace it with life imprisonment for the most serious crimes. Only then can we build a justice system that protects society while preserving the possibility of redemption, correction, and humanity.

The international community has shown the way. More than half the world’s countries have made this choice. It is time for Somalia to join them, not because it is easy, but because it is right. Because every human life has value, even those who have committed terrible acts. Because mistakes happen, and death offers no second chances. Because mental illness deserves treatment, not execution. And because justice demands more from us than irreversible vengeance.

The death penalty must become a thing of the past in Somalia. The only question is how many more lives will be lost before we make that choice.

References

Amnesty International. (2025). Death Penalty. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/death-penalty/

Geeddi SPN [@GeeddiSPN]. (2025, November 24). The death penalty should be abolished immediately. Life imprisonment would be better… [Tweet]. X (formerly Twitter). https://twitter.com/GeeddiSPN

Garowe Online. (2025, November 24). Court in Somalia’s Galkayo Sentences Woman to Death for Killing 14-Year-Old Girl. Retrieved from https://www.garoweonline.com/en/news/puntland/court-in-somalia-s-galkayo-sentences-woman-to-death-for-killing-of-14-year-old-girl

Horn Observer. (2023, June 13). Danish-Somali citizen arrested after beheading mother in Kismayo. By Horn Observer Contributor. https://hornobserver.com/articles/2256/Danish-Somali-citizen-arrested-after-beheading-mother-in-Kismayo

United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

United Nations. (1989). Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty.