Introduction

For over three decades, Somaliland has pursued international recognition as an independent state. What sets this breakaway region apart from other secessionist movements is its sophisticated approach to modern diplomacy—combining traditional lobbying with cutting-edge social media campaigns, including AI-powered Twitter accounts and passionate advocates from unexpected places.

The Lobbying Machine

Somaliland’s approach rests on careful crafting of a narrative that emphasizes stability, democracy, and governance competence, with leaders consistently highlighting peaceful transfers of power, respect for human rights, and regional contributions to security. This isn’t just talk—the region has held elections and survived as a state for the last three decades, a remarkable achievement in one of the world’s most volatile regions.

The territory’s lobbyists and campaigners in the US are pushing the notion that Somaliland deserves independence and recognition. Their efforts have paid off in remarkable ways. Senator Ted Cruz formally urged recognition of Somaliland’s independence, citing its stability, democratic governance, and strategic importance. Congressman Scott Perry introduced a bill in late 2024 proposing formal US recognition for Somaliland.

The campaign has even caught the attention of the Trump administration, with reports of Somaliland potentially granting the US a strategic military base along its coastline in exchange for recognition.

The Israeli Connection

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Somaliland’s lobbying campaign involves its outreach to Israel. In 1995, President Ibrahim Egal wrote a letter to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin seeking to establish diplomatic ties between the two countries, speaking of the need to jointly counter Islamism in the region. According to sources, Egal had sought to form a relationship with Israel in hopes of gaining recognition from the United States.

In February 2022, Africa Intelligence observed that the Israelis had dispatched several teams to inspect runways built by the Soviet Union in Somaliland. Reports suggest deeper cooperation may be on the horizon. Senator Ted Cruz, who has received nearly $2 million in funding from multiple pro-Israel lobby groups, including AIPAC, stated in his letter that Somaliland “sought to strengthen ties with Israel, and voiced support for the Abraham Accords”.

The UAE, which normalized its relationship with Israel in 2020, is acting as a mediator between Tel Aviv and Somaliland, with Abu Dhabi not only persuading Somaliland to allow the construction of a military base but also assuring that it would finance the project.

The Controversial Figure: Matt Bryden and Sahan Research

Perhaps no figure in the Somaliland recognition campaign is more polarizing than Matt Bryden, a British-Canadian analyst whose career trajectory—from UN official to private intelligence operator—embodies the murky world of Horn of Africa advocacy.

Bryden served as Coordinator of the UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea from 2008-2012, a position that gave him unprecedented access to the region’s security information. According to his Wikipedia entry, Puntland President Abdirahman Farole accused Bryden of using his position at the UN Monitoring Group to create inflated reports of munitions in neighboring regions of Somaliland in order to support his interest in the secession of Somaliland.

After leaving the UN, Bryden founded Sahan Research, a Nairobi-based think tank that positions itself as a research organization but has become the subject of intense controversy. In December 2018, Somalia’s Ministry of Internal Security banned Sahan Research from all activities in the country over reasons regarding national security, stability, and Somalia unity. The ban came after Bryden criticized the Somali government’s handling of domestic politics.

The accusations against Bryden escalated dramatically. A 2016 report from Fartaag Consulting urged the Somali parliament to investigate Sahan Research, calling it “a clear example of foreign consultants’ abusive power, mismanagement, and lack of transparency in Somalia”. Critics, including Abdiwahab Sheikh Abdisamad, director of the Nairobi-based Institute for Horn of Africa Strategic Studies, have described Bryden as “literally a warlord,” claiming he “wakes up every morning to try to find a way he can create more chaos and divisions in the Horn of Africa”.

In October 2021, Bryden was convicted of espionage by a Somali court and sentenced to five years in prison in absentia, with the court also banning Sahan Research in perpetuity from Somalia. Sahan categorically rejected the verdict, blaming Villa Somalia for being “chafed of Sahan critical reporting” and calling the trial “heavily influenced” by the presidency.

Both Presidents Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmajo” and his predecessor Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed declared Bryden persona non grata within Somalia. Yet Bryden’s influence persists through his organization’s reports, which continue to be commissioned by European governments and cited in Western media.

Most tellingly, Bryden has become an explicit advocate for Somaliland recognition, arguing that “Somaliland meets the traditional criteria for statehood recognition” and characterizing Somalia as a “failed state” while praising Somaliland as “a stable and democratic nation”. His advocacy for the Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU in 2024 demonstrates how the line between researcher and lobbyist has blurred entirely.

Critics point to Bryden’s Somali wife from Hargeisa as a potential conflict of interest that colors his work. Whether seen as a principled advocate for democracy or a mercenary intellectual profiting from regional chaos, Bryden’s role illustrates how foreign “experts” can shape narratives that influence international policy—sometimes in service of their own interests.

AI and Social Media Warfare: The Fake Congressman

The most dramatic example of AI-powered disinformation in Somaliland’s recognition campaign came to light in late October 2025, when digital forensics researcher Marc Owen Jones exposed a sophisticated influence operation. An account claiming to be “James O’Keefe,” supposedly the U.S. Representative for Georgia’s 14th District, went viral with the claim that the United States, United Kingdom, Israel, UAE, and 17 to 19 other countries would recognize Somaliland in November.

There was just one problem: Congressman James O’Keefe doesn’t exist. The real representative for Georgia’s 14th District is Marjorie Taylor Greene. The O’Keefe account used an AI-generated face, had only 217 tweets despite claiming to be a sitting congressman, and included a fake website link. Yet his post garnered 76,000 impressions, and many users appeared to believe he was legitimate.

The fake congressman attributed his claims to “African media sources”—a classic tactic of verification evasion that defers accountability to an unspecified external press landscape. Within hours, the narrative spread through numerous accounts using identical text blocks, photo cards, and hashtags (usually #AbrahamAccords). Many tagged U.S. institutions like the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Senator Ted Cruz, and the State Department—not because they were involved, but to confer authority and attract attention.

By October 26, the disinformation campaign had garnered at least 750,000 impressions and thousands of likes and retweets. Real accounts picked it up, including Bashe Omar, the former Somaliland Representative to Kenya and the UAE. Jones noted that a media outlet called MiddleEast24 went on a “Somaliland posting bonanza” after the fake congressman’s announcement, suggesting whoever ran that account was likely also behind the O’Keefe persona—trying to launder the sources of their propaganda.

The purpose appears clear: building support for recognition through manufactured momentum. If people believe recognition is imminent, governments may feel compelled to respond, either to accelerate or deny the perceived shift. False momentum can manufacture diplomatic urgency, forcing diplomatic corps to abandon traditional discretion and discuss matters publicly on social media.

This isn’t an isolated incident. Somalia’s federal government faces mounting accusations of deploying bot networks on X to target critical voices and independent media. In 10 elections across nine African nations between June 2017 and March 2018, bots were used as vessels for spreading misinformation. The sophistication of these operations is growing, with AI making it easier to create convincing fake accounts that can influence public opinion at scale.

The Geopolitical Stakes

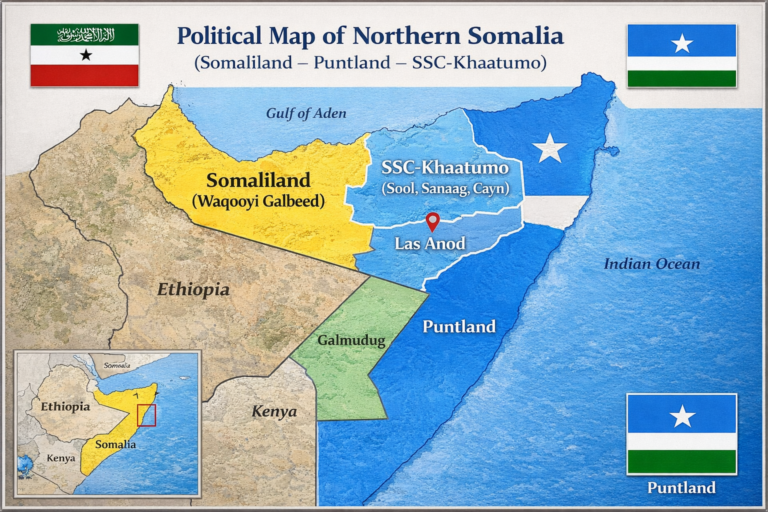

Somaliland’s strategic location on the Gulf of Aden makes it valuable real estate in global competition. The de facto state sits on the Gulf of Aden, a key global oil shipping route that has recently been disrupted by attacks from Yemen’s Houthi rebels. The expansion of Berbera Port, supported by UAE investment, and the 2024 Memorandum of Understanding with Ethiopia link Somaliland’s political credibility to tangible regional value.

The campaign for recognition has created complex regional dynamics. On January 1, 2024, Ethiopia and Somaliland signed a landmark memorandum of understanding giving Ethiopia access to the Red Sea in return for eventual recognition, making it potentially the first UN member state to do so.

The Counter-Narrative: Accusations of “Oversold” Dreams

The Somaliland recognition campaign hasn’t gone unchallenged. Saudi political analyst Salman Al-Ansari published a widely-circulated opinion piece in August 2025 titled “The Dangerous Push to Recognize Somaliland: A Threat to Regional Stability & US Strategic Interests,” which gained over 44,000 views on X.

Al-Ansari accused external beneficiaries of pushing “misleading and overly romanticized sales pitch in Washington,” painting Somaliland as a ready-made U.S. military hub on the Red Sea and a willing partner in the Abraham Accords. He described these portrayals as “childishly oversold narratives, designed less to inform than to manipulate.” His argument centered on three key concerns: that recognition would trigger a domino effect emboldening separatist movements across Africa, that it would undermine U.S. credibility in supporting a rules-based international order, and that destabilizing Somalia could threaten Red Sea security—a maritime artery through which 20 percent of the world’s energy supplies pass.

The piece sparked immediate pushback from Somaliland supporters. One X user, Barwaqo RER MIYI, responded: “Do not believe this guy writing from the comfort of Saudi. The Africans he is advising against have gone through a genocide – a crime so severe in international law and Islam.” Her comment pointed to the Hargeisa Holocaust—the 1988 bombardment campaign by the Siad Barre regime that killed tens of thousands of civilians and is central to Somaliland’s independence narrative.

This exchange encapsulates the broader information war: one side frames recognition as reckless destabilization, the other as justice for genocide survivors. Both narratives compete for attention in Washington, where policymakers must navigate between geopolitical stability concerns and historical grievances.

The Challenges Ahead

Despite the sophisticated lobbying campaign, major obstacles remain. The African Union has declined to approve recognition, concerned about generating a domino effect elsewhere on the continent. Somalia maintains that Somaliland is part of its territory and now holds one of the non-permanent seats on the UN Security Council for the 2025-26 term, giving it significant leverage to block recognition efforts.

Recently, entire communities have fallen victim to violence in contested regions, with Las Anod in Sool province facing a nine-month siege where hundreds were killed, almost 2,000 were injured, and 200,000 were displaced. This violence undermines Somaliland’s carefully crafted narrative of stability and democracy, providing ammunition to critics who argue the territory is not the peaceful success story its lobbyists portray.

Conclusion

Somaliland’s campaign for recognition represents a new model of 21st-century diplomacy—one that combines traditional lobbying with digital advocacy, strategic partnerships, and a willingness to court controversial allies. From Kenyan activists speaking Somali in Tel Aviv to AI bots flooding Twitter feeds, from Heritage Foundation policy papers to Ethiopian port deals, the campaign touches every corner of modern geopolitics.

Whether this sophisticated approach will succeed where decades of conventional diplomacy have failed remains to be seen. What is clear is that Somaliland has mastered the art of staying in the conversation, keeping its case for independence alive in capitals from Washington to Tel Aviv, from Nairobi to Addis Ababa. In the digital age, that visibility might be half the battle.

https://x.com/MiddleEast_24/status/1982881706207318182