As Somalia prepares for historic elections in 2026, the nation faces a fundamental question that has divided its political leadership, international observers, and civil society: Should Somalia rush toward universal suffrage elections, or should it strengthen the indirect system that has maintained stability, however imperfectly, through years of conflict?

This debate cuts to the heart of Somalia’s political identity. On one side stand reformers who view direct elections as a non-negotiable democratic imperative and a cure for elite corruption. On the other stand pragmatists warning that Somalia risks catastrophe by pursuing an electoral model the nation is not yet equipped to implement. Both sides claim to speak for the Somali people’s interests. Both may be right—or both may be dangerously wrong.

THE CASE FOR DIRECT ELECTIONS: Democracy Deferred Is Democracy Denied

The Argument

Proponents of direct elections make a compelling moral and practical case. Somalia last held universal suffrage elections in 1969—56 years ago. For more than half a century, ordinary Somalis have been stripped of the most fundamental democratic right: choosing their own leaders. Instead, power has flowed through opaque clan negotiations and elite bargaining that has systematically excluded the vast majority of citizens from meaningful political participation.

The current indirect system has become synonymous with corruption. Candidates spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to secure parliamentary seats through vote-buying, delegate manipulation, and elite favoritism. This system advantages the wealthy and well-connected while marginalizing youth, women, and ordinary citizens. The result is a political class disconnected from popular sentiment, more accountable to financial backers than constituents.

Direct elections would fundamentally change these incentives. When politicians must appeal to broad constituencies rather than narrow delegate pools, they become responsive to genuine public concerns: security, economic development, social services. The corruption endemic to indirect elections—the “dollarized selections” phenomenon—would become impractical at scale.

“The current indirect electoral system, which has historically concentrated power among a small group of political elites, leading to corruption, governance inef1ficiencies, and clan-based fragmentation, is no longer sustain2able.”

Furthermore, direct elections offer the only path to breaking Somalia’s clan-political stranglehold. As long as elections revolve around delegate selection by clan elders, clan identity remains the organizing principle of politics. When individual Somalis vote as citizens rather than clan members, politics can theoretically shift toward policy platforms and individual merit.

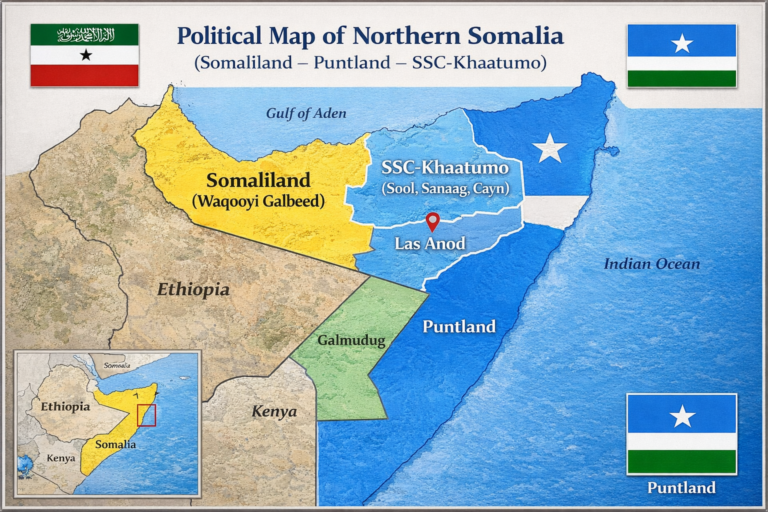

International precedent supports this argument. Both Somaliland and Puntland have implemented direct elections, demonstrating that Somali communities can organize and execute universal suffrage. Somaliland has held multiple successful presidential and parliamentary elections since 1991, proving that direct elections are not culturally impossible for Somali society.

Finally, postponing direct elections indefinitely perpetuates a legitimacy crisis. As long as Somalia’s leadership is selected by unelected delegates rather than popular vote, the government’s democratic mandate remains questionable. International partners and Somali citizens alike question whether leaders chosen through indirect processes truly represent national will. Direct elections would provide genuine legitimacy that indirect selection cannot offer.

THE CASE AGAINST: Building Castles on Sand

The Argument

Yet skeptics raise equally compelling warnings. They argue that Somalia’s enthusiasm for direct elections reflects wishful thinking disconnected from political and security reality. Rushing toward 2026 universal suffrage elections risks not democratic progress but state collapse and violent conflict.

Start with security. Somalia does not control its own territory. The Federal Government of Somalia exercises nominal authority over scattered urban centers and military outposts, while vast rural areas remain under Al-Shabaab control or disputed between federal and regional forces.

“Not only does the fed3eral government control only limited portions of the country, but many of the critical building blocks for a functioning democratic election—security, civic infrastructure, trust in institutions, and administrative capacity—are largely absent.”

How can one conduct nationwide elections when significant portions of the country are governed by an insurgent organization? Election administration requires freedom of movement, secure polling sites, trained staff, and voter protection—conditions that simply do not exist across much of Somalia. The 2026 elections would necessarily exclude millions of citizens living in Al-Shabaab-controlled areas, rendering them illegitimate by universal suffrage standards.

Moreover, the political landscape remains dangerously fractured. Federal Member States—particularly Puntland and Jubaland—have openly resisted President Hassan Sheikh’s electoral reforms. Puntland’s experience in 2023 is instructive: when the president attempted to impose direct elections, fierce local resistance threatened civil war. The traditional power-sharing agreement that ensures clan rotation—the “4.5 formula”—suddenly seemed preferable to a system that could disrupt established balances.

“In Puntland in 20234, attempts to shift from a traditional, clan-based political system to direct elections threatened to spark civil war.”

These tensions have not been resolved. As recently as 2025, opposition leaders including former presidents have rejected the direct election process as illegitimate, suggesting they may organize parallel votes. This signals not a nation united behind electoral reform but a deeply divided polity where electoral change could trigger state fragmentation.

The institutional capacity argument is equally damning. Conducting direct elections requires voter registration systems, polling infrastructure, trained election officials, security deployment, and dispute resolution mechanisms. Somalia lacks all of these at scale.

“Somalia’s electoral infrastructure is virtually non-existent.”5

Voter registration alone requires identity documentation, geographic databases, and administrative systems that barely function. Meanwhile, the history of elections in Somalia shows that even indirect elections—logistically simpler—have repeatedly missed deadlines, descended into violence, and required international intervention to complete.

Skeptics also point to the corruption risk. While critics argue direct elections would reduce vote-buying, this fundamentally misunderstands Somali political economy. Clan elders who currently control delegate selection would likely transition to mobilizing clan members as voters. Wealthy candidates would simply shift their spending from bribing delegates to bribing voters. Research on vote-buying in developing democracies suggests that direct elections often increase electoral corruption as candidates pursue mass-scale purchasing power rather than small elite manipulation.

“The practice of vote-buying, a major complaint in the6 2016 election, was expected to persist and potentially increase in scale.”

Finally, there is the question of motivation. Why is President Hassan Sheikh suddenly pushing for direct elections? Skeptics note that he was elected indirectly in 2022 by just 327 lawmakers—hardly a popular mandate. Some observers suspect that direct elections, if implemented favorably, could provide him with perceived legitimacy for a controversial second term or even constitutional extension. The push for electoral reform may reflect personal political calculation rather than democratic principle.

“The president started to review Somalia’s contested constitution, signalling a possible extension of his tenure in the name of conducting one-person-one-vote elections across the country.”7

THE MIDDLE GROUND: Staged Transition and Patient Democracy

A Third Perspective

Some analysts propose a middle path: pursuing direct elections not as a binary choice but as a staged, incremental transition. Rather than holding nationwide universal suffrage elections in 2026, Somalia could experiment with direct elections at municipal and local levels while strengthening institutions for eventual state and federal contests.

This approach has merit. Puntland’s successful local council elections in 2023 demonstrate that direct elections are feasible at smaller scale and lower stakes. Starting with municipal contests allows Somalia to build voter registration systems, train election administrators, develop dispute resolution mechanisms, and generate experience without betting the entire state on a single electoral cycle.

“Future research is needed to understand challenges to the transition process from the perspectives of stakeholders in south-central Somalia.”8

Advocates of staged transition argue this addresses security concerns. Direct elections in secure urban areas and liberated zones can proceed while areas under insurgent control gradually return to government administration. As security improves, direct elections can expand territorially. This prevents the illegitimacy of excluding millions from voting while allowing genuine progress toward universal suffrage.

Importantly, staged transition also permits political consensus-building. Rather than imposing direct elections unilaterally, incremental approaches give federal and state leaders time to negotiate power-sharing arrangements that preserve important balances while accommodating democratic reform. This reduces the likelihood of state fragmentation.

“These issues are deeply interconnected and cannot be separated. Completing the constitution hinges on achieving political consensus among Somali stakeholders, while conducting direct elections depends on eliminating armed groups that control significant parts of the country. Both require political reconciliation—or, more precisely, political consensus.”9

The middle ground acknowledges that direct elections are a legitimate goal—but one requiring patient institution-building rather than rushed implementation. Democracy cannot be imported or imposed by timeline; it must be constructed carefully from existing political foundations.

WHERE THE EVIDENCE POINTS

What does Somalia’s own experience tell us?

The 2016-2017 and 2021-2022 electoral cycles demonstrate both the resilience and fragility of Somalia’s political system. Despite enormous challenges—security threats, political crises, tight timelines—Somalia completed indirect elections and peacefully transferred power. President Hassan Sheikh was elected in 2022 through indirect processes that, while imperfect, commanded enough legitimacy to establish a functioning government.

Yet these same cycles revealed systemic weaknesses. Repeated missed deadlines, violence targeting candidates and officials, corruption scandals, and elite resistance all characterized recent elections. These problems are inherent to the current system—but they also reveal how difficult electoral management is in Somalia’s context. Adding complexity through direct elections will not solve these problems; it may amplify them.

The regional comparison is mixed. Somaliland’s electoral success is genuine but occurred in a context of greater territorial control, stronger institutions, and more consistent international support than Somalia enjoys. Puntland’s partial progress toward direct elections came with significant resistance and political risk. Neither precedent clearly demonstrates that Somalia as a whole can successfully implement nationwide universal suffrage.

THE STAKES

Ultimately, this debate is not merely technical. It concerns fundamental questions: What does democracy mean in a post-conflict society? Must universal suffrage be immediate to be legitimate? Can incremental electoral reform succeed, or does gradualism perpetuate elite capture? How should the international community balance pressure for democratization against respect for local political realities?

There are no easy answers. Direct elections represent a genuine democratic aspiration—and a genuine risk. Postponing universal suffrage perpetuates an undemocratic status quo—and preserves hard-won stability.

The honest truth is that Somalia faces a dilemma with no perfect solution. Rushing toward direct elections without adequate preparation risks state collapse and reversed democratic gains. Yet indefinitely deferring universal suffrage denies Somalis their fundamental right to vote and perpetuates corrupt elite politics.

The way forward likely lies between these extremes: pursuing direct elections at municipal and local levels while patiently building institutions for eventual state and federal contests. This approach honors democratic aspirations while respecting political reality. It allows Somalia to make genuine democratic progress without gambling the nation’s stability on a single electoral cycle.

But such nuance rarely prevails in politics. Somalia’s leaders must soon choose: continue gradual reform, or take the leap toward 2026 universal suffrage. The choice will define Somalia’s democratic future for generations to come.

- https://www.hiiraan.com/op4/2025/feb/200397/somalia_s_democratic_future_why_direct_elections_are_non_negotiable.aspx ↩︎

- https://www.hiiraan.com/op4/2025/feb/200397/somalia_s_democratic_future_why_direct_elections_are_non_negotiable.aspx ↩︎

- https://wardheernews.com/from-villa-somalia-to-virtual-democracy-the-fantasy-of-one-man-one-vote/ ↩︎

- https://www.eip.org/the-institute-at-10-democracy-new-and-old-averting-an-electoral-crisis-in-somalias-puntland-state/ ↩︎

- https://wardheernews.com/from-villa-somalia-to-virtual-democracy-the-fantasy-of-one-man-one-vote/ ↩︎

- https://riftvalley.net/publication/addressing-contentious-issues-on-elections-in-the-constitutional-review-process/ ↩︎

- https://hornobserver.com/articles/3488/Can-Somalias-upcoming-and-disputed-elections-save-the-country-from-plunging-into-further-crisis-Analysis ↩︎

- https://www.prio.org/publications/13511 ↩︎

- https://www.hiiraan.com/op4/2025/mar/200921/direct_elections_in_somalia_illusion_or_reality.aspx ↩︎